There’s a club you’re not in, but you keep showing up to the door anyway. You put the look together—intentionally mismatched, just the right amount of worn-in, maybe a little borrowed genius from a dead designer. You do the work. You wait in line. The bouncer scans you. Maybe you get a nod, a shrug, or nothing at all. You go home and rework your outfit. Try again next week. Because sometimes just wearing the right outfit feels like enough. Like the look alone could be your ticket in.

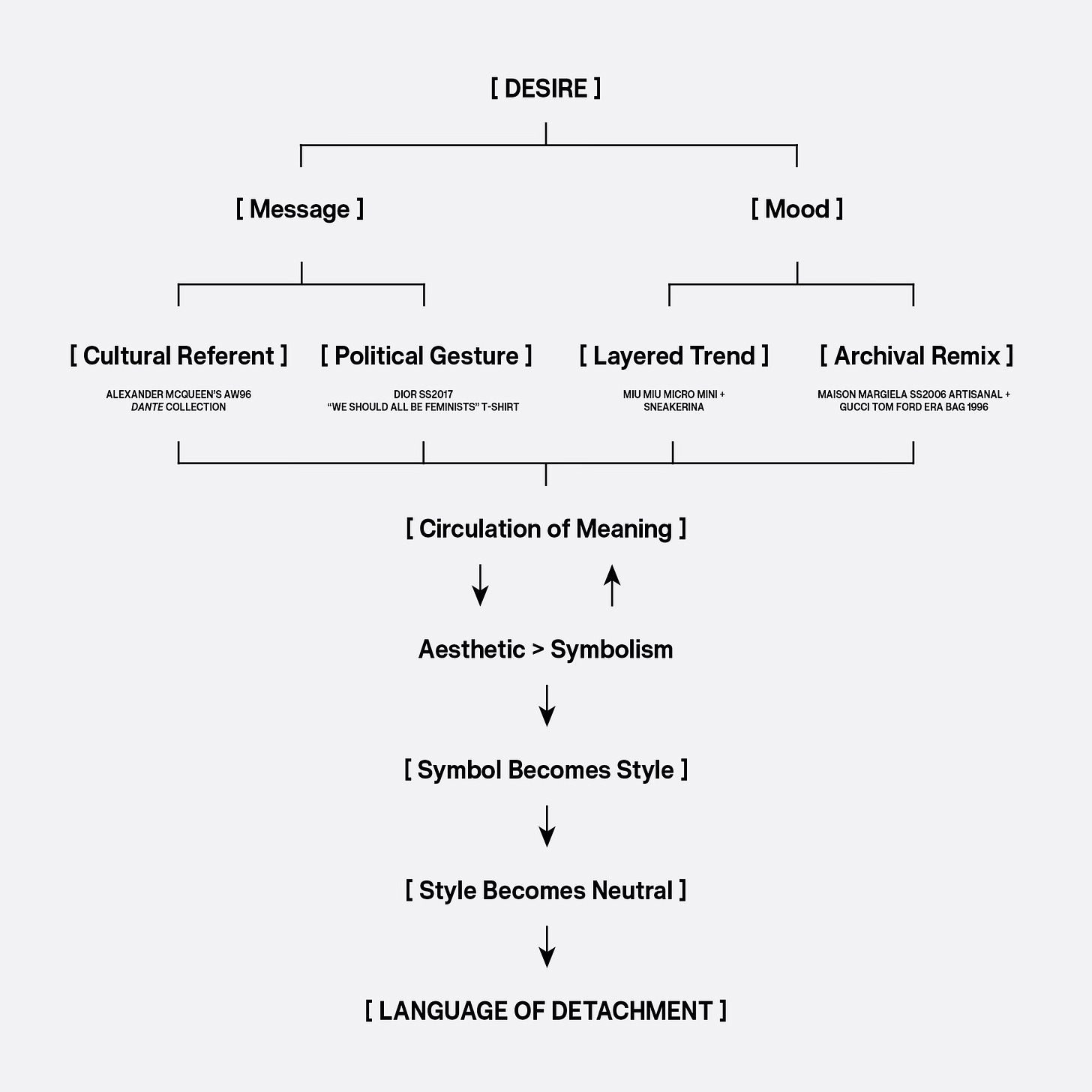

What happens when fashion starts borrowing symbols that were never meant to be decorative? A religious cross, a sari dress, a national flag—objects loaded with history, identity, belief—suddenly show up on runways. But they’re not always there to say something. Sometimes they’re just... there. Not as messages, but as moods.1 Fashion has a way of making symbols aesthetic first, symbolic second—if at all. Instead of pointing outward to a meaning, these references start looping back in on themselves. They become part of fashion’s own language: self-referential, slippery, endlessly customisable. Not necessarily empty, but definitely different. Like the sticker over the camera on your phone you got in the club you went to, and still wear.

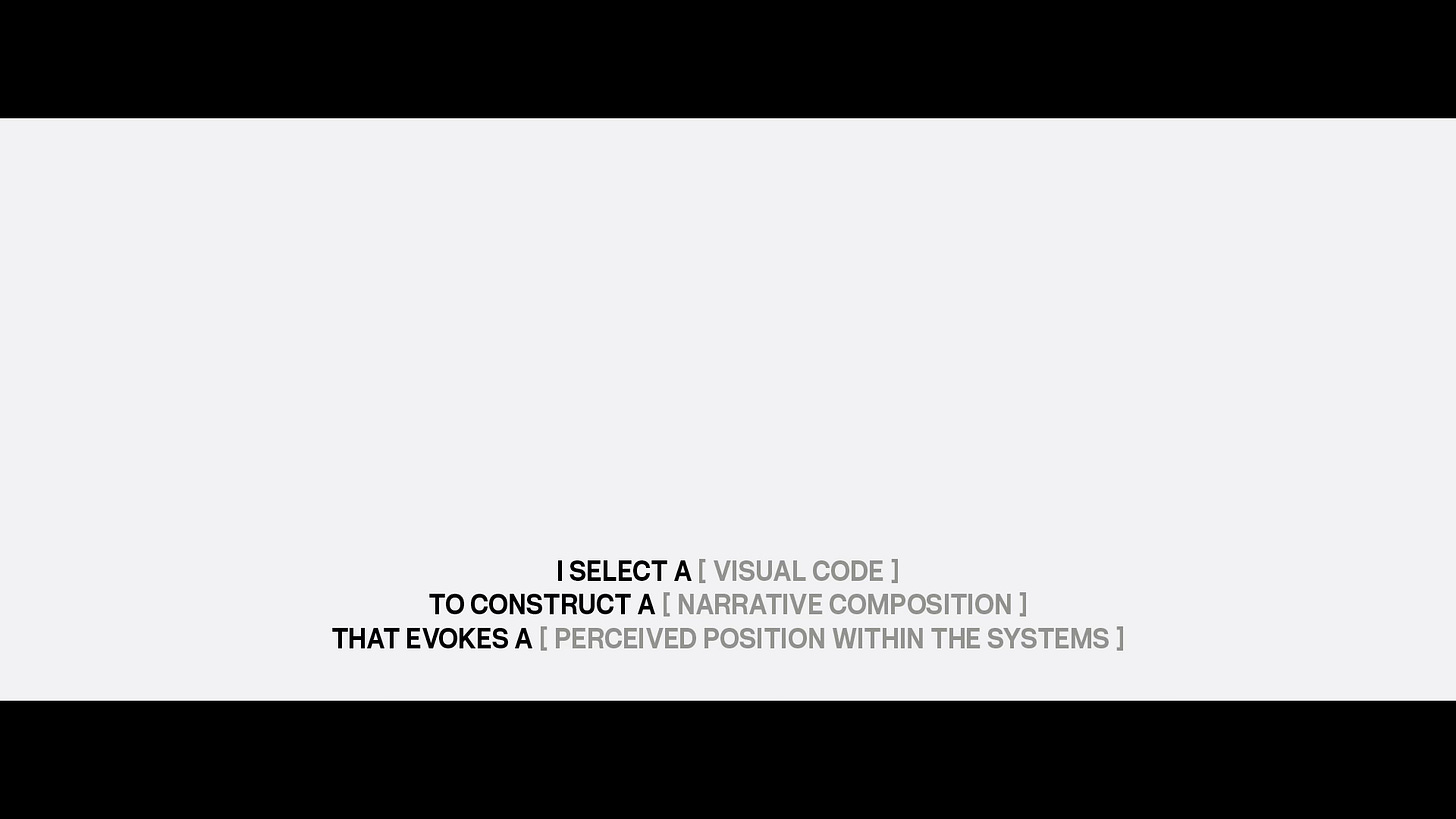

Is fashion still saying something, or is it just referencing itself on repeat? In the past, style had rules—colour palettes, silhouettes, combinations—that pointed somewhere: to a culture, a class, a subculture, a time. But today, postmodern fashion doesn’t really play by this rulebook.2 It skips chapters. It references things that were already referencing something else. A 70s revival jacket styled with Y2K sunglasses and a medieval corset? Sure. Why not. The result is a kind of free-for-all aesthetic that doesn’t need to explain itself. The need to “mean” something has been replaced by the need to look like something. And that “something” is often filtered through pop culture or theory, not lived experience. You dress for the line outside the club, not the dance floor.

This shift has often been framed as democratising—style once reserved for elites now filters downward, becoming accessible to all. And in many ways, that’s true. But what we call “democracy” might just be consumer ideology in disguise. What looks like freedom of choice could just be freedom to consume. Everyone’s invited, but not everyone gets in.

Alessandro Michele refers to himself as an art archaeologist—historicist of garments—rather than a creative director, arguing that clothes are meaningless without historical context. It sounds noble. Intellectual. Almost radical. And yet, these kinds of statements tend to function less as ideology and more as branding. Everyone wants to be more than “just” a designer now. We’re image makers, style architects, visual poets, sometimes all at once—especially when there’s a job opportunity involved. Roles in fashion are passed around like club stamps—visible for the night, then fading by morning, only to be re-applied to someone new. They promise complexity, collaboration, innovation. In reality? It’s just a different DJ spinning the same tracks.

In fashion, “cool” isn’t a look—it’s a password. A quick scan and a question: “Who’s playing tonight?” Not to chat—just to see if you belong. The fancy words designers use don’t just describe style—they help create its value. Fashion magazines play a big role in this too. The more “high-status” the magazine, the more serious and toned-down the language—because it’s written for readers who are seen as socially elite.3 You don’t just wear the look, you’ve got to know the lore.

But every now and then, someone messes with that system. Take those dresses that became a symbol of innovation—not because they followed the rules, but because they didn’t. While the industry still clings to old-school production methods like CMT (Cut, Make, Trim), these designs pushed for something else. They broke down how clothes are made and worn, nodding to a history of designers in the ’80s and ’90s who tried to bend the system. But today, that same aesthetic comes with its own line to the club.

This kind of disruption doesn’t tear the system down—it just learns how to market itself better. A tear becomes a signature. A raw hem turns into a talking point. Detachment becomes design language. And just like that, the rejection of fashion becomes fashion.

These dead ends are fraying on the edges, and what’s left behind isn’t so much a trail forward as it is a loop back into old ideas, dressed up in new fabric. There’s still much potential in trying to break beyond the runway and into the reality of everyday life—a promise of getting into the club, perhaps. But the inside of the club is harder to imagine when the bouncers outside keep turning away anyone who doesn’t know who’s playing.

I’ve waited in that line too—adjusted my look, dropped the right names, knew the line up. I got in, and felt recognised. But still, it often felt like a deafening silence. The sound of the loud speakers resonating loudly in the club’s walls. You almost can’t hear a thing, but somehow, you still move to the rhythm. Because that’s what everyone else is doing.

I remember being barely 21, interning in Paris, desperately trying to get into that club. I dreamed of fashion. I admired every stitch, every button, until I became obsessed with the idea of becoming a part of this world. So yeah, I showed up—watching runway shows, flipping through magazines, pretending I had it all. But when I got in? The reality hit like the bouncer at a club that doesn’t care how great your outfit is. It wasn’t about dreams—it was about the invisible things nobody talks about, with enough abuse, and exploitation to fuel the runway.

My dreams were shattered by the harsh reality of an industry that promises so much but runs on unpaid interns and broken backs. Sure, maybe I saw it all wrong and wasn’t grateful enough—maybe that kind of exhaustion was the price. A direct addition of my name to the guest list.

We all follow this line to a club like a sacred path. We suffer now, so maybe one day, someone important remembers our name. More broken we are, the closer we are to the “truth”. Until we start to believe that the sacrifice is the price. That exhaustion means we’re doing it right. That silence is a sign of respect. But after a while, I decided not to follow that path anymore. I left Paris with a fear to dream. I still carry that tiny urge for revenge—not on a person, but on the system that sold the dream so well, only to hand me the bill. And even now, when I walk past the line outside that same old club, I can’t help but glance over—just to see who’s waiting, who’s pretending not to care, and who’s still hoping to hear their name at the door.

So yes, revisiting the past can still feel sharp—still useful—but mostly it just reminds us how little has changed. The fact that forty-year-old critiques still cut through today’s fashion system says less about their timelessness and more about fashion’s hesitance to self-reflect. And that’s the real warning sign.

The club still lets you in—but only if your rebellion fits well. And the rest of the club-goers? They’re still fixing their outfits outside, wondering if they should’ve frayed the edges more.

Baudrillard, J., Simulacra and Simulation (1981), Glaser, S. F. (translation), The University of Michigan, Michigan 1994.

Tseëlon E., Jean Baudrillard: Post-modern Fashion as the End of meaning in a book A. Rocamora a A. Smelik (eds.), Thinking Through Fashion: A Guide to Key Theorists, I.B. Tauris, Londýn 2019, p. 257.

Bourdieu, P., Delsaut, Y., Le Couturier et sa Griffe, in a magazine Actes de La Recherche en Sciences Sociales, Paris 1975.